Founded 1980

Chair:

Secretary:

Treasurer:

Graham Smith

Jan Thompson

Graham Mumby-Croft

had seen at Dover and as our mother was now living in Whitstable it was more than ideal, especially with Dover station being at the foot of the Western Heights.

Soon after our return to college, each tutor saw us individually to discuss their recommendation as to our first posting; that would then be conveyed to the personnel representative from Headquarters who would also see us and make the final decision. My tutor told me of his recommendation; I cannot even remember what it was. I said I wished to go to Dover, he replied ‘there are no vacancies!’ I advised him I would still ask for it. When I met the headquarters representative from personnel, he advised what my tutor had recommended. I replied 'I know but I want to go to Dover, I have been on attachment there and I was made most welcome and was impressed with what they were striving to achieve.' He pondered for a minute, checked his notes, and said 'we do hold a lot of credence as to what your tutor recommends but we do have vacancies at Dover, so in your case, that is where you will be allocated.' I was overjoyed but it also reaffirmed my belief that ‘the experts’ do not always use the power and Influence as they should, and you have to stand up for yourself. In fact, two of us were posted to Dover.

I took up my post at Dover in April 1965 along with another colleague, also a Bob. We were made welcome by the Governor, David Gould, who explained the philosophy of the establishment and that the ‘lads’ were housed in 6 separate units, called houses and named after the Cinque Ports, and each held a slightly different type of lad. He told Bob he would be taking charge of Walmer House, which held the less sophisticated and better educated and I would take over Hythe, which held the more sophisticated, more heavily convicted and more violent group. The one advantage of Hythe was it was a new purpose-built unit on the far side of the parade ground and adjacent to the education centre and the chapel, and no longer below ground, whereas the original ‘casemates’ were all dug out of the chalk and underground and comprised 3 long chambers, 2 as dormitories and the centre one a staff office and recreational area for the inmates. The accommodation was all in dormitories and each unit held 50 lads. In the ‘casemates’ this was 25 per dormitory, but in Hythe, it was four dorms of 13 beds in each. Before my time at Dover, one of the Bonham-Carter’s was on the staff as a housemaster. Apparently, he was pretty hopeless in the role and had been encouraged to look elsewhere for work. He declined and carried on. So Governor instructed that no more lads where to be allocated to his unit. So when the last of his current lads had been discharged, he finally got the message and resigned.

The Governor had attended a Senior Course in criminology at the Institute of Criminology in Cambridge, which had as one of its themes, the rising re-conviction rate of discharges from Borstal. This had led to a proposition from David that Dover should be directed by Cambridge as to its reformative programmes and then evaluated as a research project. David believed that training at Borstals tended to have regimes which were a mixture of Home Office official policy modified a little by individual governors, whereas he believed there was a need for individualization of training. This fitted closely with the view of F. H. McClintock, Fellow of Churchill College, and lecturer in Criminology at Cambridge. David received support from him and that led eventually to funding from the Home Office.

Every establishment has what is called by prisoners, ‘The Block’ or ‘Seg’ which is a separate group of cells set aside for those undergoing punishment for acts of indiscipline. The Deputy Governor, Bill Fingland, was in sharp contrast to the Governor being a dour Scot, but he was a caring man, and they made a well-balanced pair. The lads gave him the nickname ‘Down the Block Jock’ as he was a stricter disciplinarian than the Governor.

All staff in those days were entitled to a quarter, they were free in theory but we all had some money docked from our salary, it was called ‘rent in lieu.' Only the civil service could make something so mundane seem incomprehensible. The housing provided varied in size and quality according to rank. Technically I was entitled to a 3-bedroom house; fortunately, there was what was termed a ‘matrons flat’ available, only 50 meters from the Borstal gate, with 2 bedrooms, a sitting room, kitchen and bathroom. It also came with free coal and a free allowance of so many units of electricity. As there was an ‘officers mess’ just 50 meters away where I could obtain a cooked lunch, I was well set up. The town was ¾ of a mile away and down a very steep road, which was technically closed due to an unsafe tunnel, but as it was the shortest route I used it as the alternative road twisted and turned and was much longer. All a bit tiresome when dragging shopping back up, so the only other necessity was a car, but as I did not have a driving licence, that had to wait. I was very comfortable in my flat and never had to pay a fuel bill. That changed. Two years on a Canadian called Tom arrived having come to England to make his way in the English Prison Service, and after training was posted to Dover and was living in the officer's mess. We would meet up at lunch; I knew the mess conditions were not good, so after a while, I offered him the spare room in the flat, which he gratefully accepted. I was aware that Canada was a cold country in winter. However, I discovered I had suddenly started to receive electricity bills. I started to investigate this unwelcome development only to discover that Tom was leaving the electric heater in his bedroom on all day, even when he was on duty. We had a few words and adjustments were made accordingly.

The son of a member of staff repaired and sold damaged vehicles. He had a 600cc Renault 8 for sale, so I took a few driving lessons and then took my driving test in Folkestone, so had to be well versed in hill starts. Having passed I had to find the money, and then I owned my first car. Fortunately, traffic was lighter in those days, even in Dover, so there was plenty of opportunities to embed my new skills in driving.

The Governor was very much a self-educated man and very ambitious. He was also very brave as he had personally climbed halfway down the high chalk cliff to rescue a Borstal boy who was trying to escape but had been trapped on a ledge and was fearful of trying to climb down any further. (Technically he was only absconding as the Home Office had decided that young offenders only absconded. In reality, you could only abscond from an open prison, but this was applied to all young offender establishments. No doubt it made the Home Office figures look better.) He was posted there in 1959 from Latchmere House Allocation Centre for Young Offenders as a Governor 3, but because the inmate population held at Dover had increased the Department proposed to upgrade the post, David had passed his Board for Grade 2 so asked to stay at Dover in the higher grade. This was granted.

The original agreement with Cambridge had stipulated that the after-care provision also needed to be part of the reform and research. The Prison Department took ages to decide whether it would back the initiative but removed the after-care element as it claimed it was too big a task to take on, but gave support and funding for the in-house reforms which placed all the emphasis on the staff at Dover.

Every new arrival had a dossier compiled from the information in his record and an initial interview. These were locally known as ‘Joca’s’ taken from the file cover they were kept in. Every member of staff was involved and had an allocation of lads to interview and write up. All this was in addition to the existing monthly review by house staff which counted towards the four steps progress through the grades each lad had to go through to earn his discharge. Each step was formally recognized by a different colour tie, (blue, red, green, brown.) and verbal feedback had to be given each month to every lad by the housemaster in a private interview. Clearly, the two schemes overlapped to a degree and fed into each other. The whole scheme was taken seriously by the majority of staff. The Institute appointed a research assistant (an ex-Probation Officer called Tony Bottoms) to the establishment and he visited regularly both to advise and monitor the programme. I got to know him well which was to be very useful in later life, though I did not know that at the time.

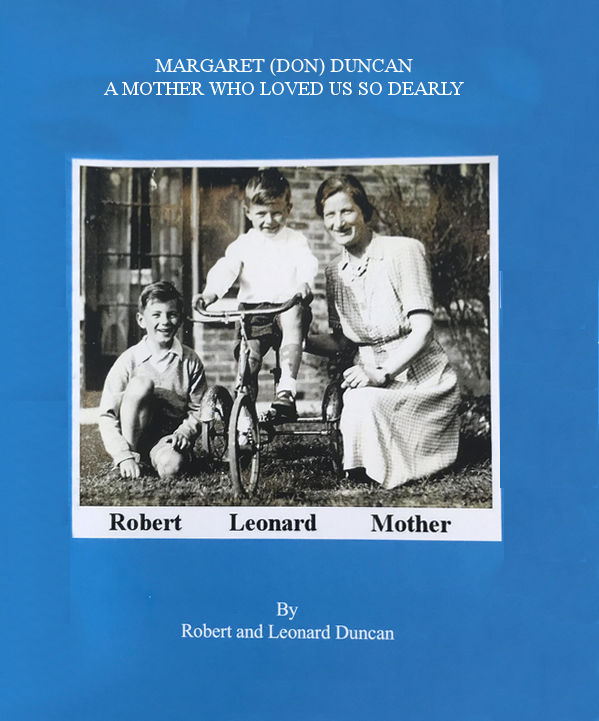

BOB DUNCAN

Dover Borstal to be continued in the Autumn Edition, which will be part 6 of Bob’s memoirs

Autobiography.

DOVER BORSTAL continued

After the Christmas break, we returned and were advised we would soon be going on a second short attachment. I was allocated Dover Borstal with Howard, not my favourite person; but as we were to go straight from college to Dover, the one advantage was that he owned a car. He was also ‘an expert on good food!’ and an ex-marine who trained in Deal. For the whole dreary journey, he kept telling me about the intricacies of ‘double de-clutching' and how good he was at it. As I did not drive it was all lost on me! This was interspersed with a description of all the ‘posh ‘restaurants we could visit in the area.

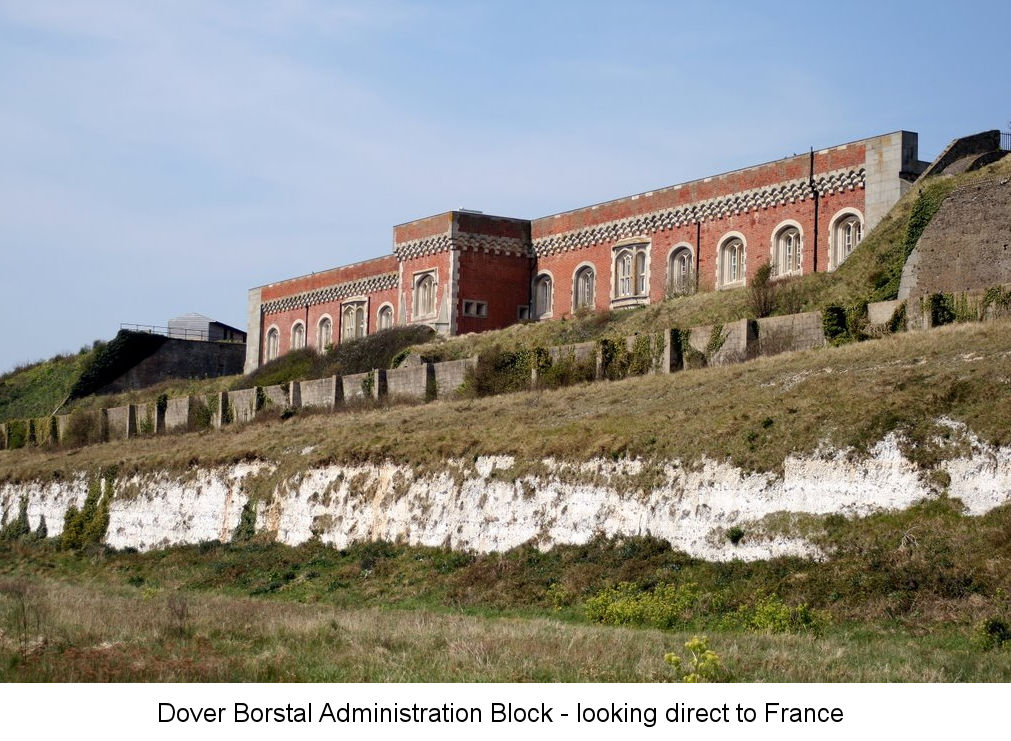

Dover Borstal is sited on the Western Heights, the hill directly opposite Dover castle; in between is the valley which is Dover town and port. Dover Castle is Norman whereas the fortification which became the Borstal was constructed in the 17th and 18th centuries as a lookout and initially a defence against Napoleon and was always known as the Citadel. It is located high above the seaport on the white cliffs of Dover overlooking the English Channel. On a clear day, from the administrative offices overlooking the sea; one could read the clock in Calais. It was surrounded by a brick-lined dry moat, some thirty feet deep and thirty feet across. It included a vast system of tunnels, forts and underground dormitories all linked to protect the country from invasion and to protect the port of Dover. In all, it was reputedly reported to be the strongest and most elaborate fortification in the country. The army withdrew from the forts gradually from 1956-61. I explored the whole of the underground tunnels and forts in my early days in Dover; they were impressive, to say the least. Not long after that, the entrance was boarded up as it was decreed they were unsafe.

The Borstal element was a moated garrison with a drawbridge entrance and central parade square and 4 large dormitories below ground level carved out of the chalk: each capable of housing fifty lads. There were also two more modern dormitory units set above ground. The housemaster I was shadowing decided to take some leave within a couple of days of my arrival and left me temporarily in charge. The staff were very helpful, and I volunteered to play rugby with Borstal team who had an away match against a local team. On one occasion when I was at home in Whitstable but dashing back to play rugby with the Borstal team, Leonard joined and played as well. I liked all I