Founded 1980

Chair:

Secretary:

Treasurer:

Graham Smith

Jan Thompson

Graham Mumby-Croft

Issue No. 89 Autumn 2023

Peter Atkinson

Over the Wall - (Part one of three)

By: Peter Atkinson.

Sat astride the top of the inner fence of the Cambridgeshire top-security Whitemoor prison, was an inmate in the process of trying to escape. As unarmed staff arrived in an attempt to stop him, the inmate pointed a gun and shot one of the pursuing officers in the leg. That was the frightening reality of an incident that unfolded at ten minutes past eight one evening in September 1994. This more than illustrates that escapes by dangerous inmates from British prisons may be portrayed as dramatically thrilling for consumption by the general public but within the Service they are no joke. To non-prison people there is something romantic about escapes from custody that are often glamorised by movies and TV dramas. Films portraying escapes are made out to be exhilarating and fun, but for those

charged with keeping prisoners safely behind bars, there is nothing enchanting about ‘one away.’ The 1980 film about John McVicar’s escape from Durham starring Roger Daltrey and Adam Faith; the 2008 The Escapist starring Brian Cox and Joseph Fiennes; the 2005 TV series Ronnie Biggs – the Great Train Robbery and the 2017 film Maze starring Tom Vaughan-Lawlor, are all good examples. There are many more of course but we don’t need to go to the movies to appreciate the drama of escapes, given that a number of high-profile breakouts in our own British prison system over the years, have given us more than enough to chew on. It is worth remembering however that for every serious prison escape, there are dozens that have been successfully foiled by staff. Since the second World War there have been countless escapes, but I would argue that only around fourteen have been, what might be termed, notorious ones.

A good starting point from the 1950’s is the escape by Alfred George Hinds (Alfie). Highly intelligent and becoming a member of Mensa, Alfie had a tough upbringing. When seven years old, he experienced the death of his father when his criminal Dad died in custody during the process of receiving 10 lashes from a ‘cat-o-six tails’ as a punishment. After being brought up in a children’s home, he was into crime early. His first custodial sentence as a delinquent was served in a Borstal from which he escaped - that was not difficult in those days. Becoming a consummate and persistent safe breaker, it was not long before the law caught up with him and he was sentenced to 12 years imprisonment in 1953, aged 36. He had been accused of taking part in the celebrated robbery of the prestigious Maples furniture store on Tottenham Court road. It is probable that he was wrongly convicted for that crime and had actually taken no part in it.

For his alleged role in the Maples store robbery, he was first sent to Wandsworth prison and then onto Nottingham. Two years into his sentence, he planned an escape along with a burglar from Islington called Patrick ‘Patsy’ Fleming. It was July 1955 on a Saturday evening when the two men gained access to an old padlocked stoke hole (a shute down which coal was sent to a furnace) on their wing with a duplicate key. They lowered themselves down the shute, through a grate and out into the yard. Finding two doors stacked against a wall, they balanced one on top of the other and used that to scale the wall and drop 20 feet to the street below. By pre-arrangement they linked up with an accomplice driving a lorry loaded with loose oranges and after burying themselves in the fruit they managed to pass through a manned police road block and away to the Brixton area of London. Alfie lived a relatively normal life in Ireland until he was arrested by Scotland Yard’s Flying Squad, having been at liberty for 248 days.

During his trial whilst on remand, he attended the High Court at the Old Bailey, escorted by two prison officers. His brother Albert who was not in prison, had managed to fix a hasp and staple to one of the Court lavatory doors, just before Alfie’s attendance at Court. With some cunning subterfuge, Alfie managed to lock his two guards into that toilet with a padlock that Albert had hidden close by. He casually wandered through the court and out into Fleet Street and away. He was only free for five hours, before being seized in Bristol whilst trying to catch a plane to Dublin. Being regarded as a serious risk, he was designated a Class A escaper and placed in a prison uniform, which at the time had large white patches both on the trousers and upper tunic. Later in prison service history, white patches were replaced by yellow. He ended up at the then top security Chelmsford prison, but it wasn’t long before he fashioned a further escape in June 1958 with a fellow prisoner called George Walkington. In his mid-30’s, George was serving a seven-year sentence for what was known as ‘jump-ups’. In the 1950’s, goods were often transported on open flat bed lorries with low sides. Along with an accomplice, people like George would jump up onto the back of these wagons at traffic lights or as they rounded corners and throw off boxes of cigarettes for example, from the moving lorry before jumping off and retrieving the booty. Back in the prison during the more relaxed Sunday routine, the pair tricked their way onto the lower ground floor that gave access through the clothes store, onto a corridor and eventually out into an open yard. They had a duplicate key for a set of gates that led direct to the perimeter wall, but the key did not work. In the open yard there was a coal bunker and close by there were two wheelbarrows. They stacked them on top of each other and managed to reach the top of a wall. Alfie slipped at one point and broke his glasses. Despite this handicap the pair worked their way along the wall and eventually reached the main perimeter, that was covered in barbed wire. The wire was eventually negotiated with a 25-foot drop to the ground outside. The wall base was wider than the top and as Mr Hinds tried to clear the base, he tumbled and seriously damaged his leg. Limping badly, the pair made their way through an adjacent school at the back of the prison but were seen by a caretaker who phoned the jail. The alarm was raised, but it was too late in that they managed to rendezvous with an accomplice driving a Morris Minor that carried the pair to London. Mr Hinds then caught a boat to Belfast and evaded capture for two years before being caught in 1960 and sent to Parkhurst. Mr Walkington avoided arrest for 32 months but was eventually arrested at Wimbledon dog track.

Mr Hinds escape history was sensational at the time and he earned himself the sobriquet ‘Houdini Hinds.’ The papers covered his exploits in lurid detail with such headlines as ‘Escaper Extraordinary.’ A TV programme covered his Chelmsford escape in a 1980 drama. He was eventually released from Parkhurst in 1964, becoming somewhat of a celebrity where he adopted a career challenging many aspects of criminal law as well as trying to take the Prison Commissioners to court. He died in St Hellier hospital Jersey in 1991 aged 73, and even earned a small obituary in The New York Times.

* * *

The first of the Great Train robbers to escape from prison was the handsome, book maker Charles Frederick Wilson (Charlie). The sequence of events in the train robbers case was that they hi-jacked the train on the 8 August 1963, the gang were captured and then tried in April 1964 and Charlie escaped from Winson Green in August 1964. Charlie was born to a decent family in 1932 but decided to follow a criminal career with one crime following another. That was until he hit the big time with the huge theft of £2.6 million from the Glasgow to London mail train, as it travelled between Leighton Buzzard and Cheddington at three o’clock one Thursday morning. (£2.6 million in 1963 was equivalent to around £50 million today.) Charlie, along with most of the other 14 gang members, received 30 years and was sent to Winson Green awaiting onward transmission to a more secure jail. For a suitable payment there was no shortage of fellow criminals who were more than willing to help the train robbers with their escape plans. Perhaps Charlies escape might be described as the most disturbing. The authorities could never be absolutely certain how he got out, but the preferred theory was that a gang of three climbed over a low wall into the grounds of Birmingham prison. With a rope ladder they scaled a higher wall that gave access to the living units. With a set of the correct keys, they successfully made their way through the main prison to Charlies cell block. Located on the ground floor, the gang opened the door to his cell with the correct key. They gave him a roll-neck sweater, some black trousers and a balaclava and the group left the way they came in. A night patrol Mr Nichols was coshed and left unconscious, bound and gagged with a head wound as the escapees departed locking the gates behind them. The balaclava for Charlie may have been a means of avoiding identity if the gang had been spotted by staff. By avoiding being identified, it would have been the devils own job to find out who had actually escaped given that all the cell doors and windows were intact. Such escapes sound exciting, but for the prison staff involved, there is little excitement in being seriously assaulted. There would be no excitement either for the Governor having to pick up the pieces. It was never known from where the keys came, with one unproven theory that it was an ‘inside job’ involving a member of staff.

At the time of the train robbery, Charlie was 31 years of age. His escape took him to Canada and after four years on the run he was eventually captured in January 1968, living a normal family life with his wife and children in the small town of Riquard, 40 miles from Montreal. He was returned to the UK and remained in custody until 1978 having served a number of years in Durham. He became the last of the train robbers to be released after which he went to live in Marbella and reputably got mixed up in the drugs trade. A hit man visited his villa one day and shot him next to his swimming pool. He was aged 81.

* * *

Ronnie Biggs was the next of the train robbers to make his escape eleven months after Charlie. This time it was Wandsworth prison and the escape was subsequently turned into a film. Ronnie was born in London in 1929 and joined the RAF from where he was dishonourably discharged for desertion. He lapsed into crime and during one term of imprisonment at Wandsworth, he met Bruce Reynolds, generally reputed to be the master mind behind the train robbery. After release and with a wife and three children, he tried to quit crime. But, in need of money for the deposit on a house, he happened to meet an old train driver who knew how to bring a train to a halt without raising an alarm. The plot for the Great Train Robbery began to materialise. Interestingly enough, the old train driver who allegedly inspired the robbery in the first place, was never identified.

With enough money to persuade others outside and inside prison to be part of the organised heist, his escape was well planned. At around three o’clock on a Thursday afternoon in 1965, as ten inmates were out on one of the exercise yards, a stocking-masked head appeared over the wall and uncoiled a rope ladder. This was the signal for Ronnies departure, but before he could get to the ladder, two other inmates who were not part of the plot beat him to it and scaled the wall first. As Ronnie made his way up the ladder followed by an accomplice, the remaining inmates on the yard forcibly held back the four officers overseeing exercise. One inmate called Brian Stone who was in on the plan, told his story many years later in 2014, confessing that he had prevented the officers from stopping the escape. For his troubles, he got 12 months added to his sentence. Robert Anderson aged 27 serving 12 years for robbing a post office and Patrick Doyle aged 23 serving 4 years for conspiracy to rob, were the uninvited ones to make it over the wall. Eric Flower aged 37 serving 12 years for armed robbery who had been part of the escape plan, was the fourth of the men to make it onto the top of a pre-planned furniture lorry parked against the perimeter wall. All four dropped into the main compartment of the lorry and made it to a couple of waiting cars, one of which was the famous green Ford Zephyr. A shot gun, amongst other things, was found in the lorry and presumably would have been used if regarded as necessary. A prison officers wife in one of the prison houses overlooking the prison wall, saw much of what went on and was a useful witness in describing events of the immediate getaway. The logbook that recorded Ronnies movements whilst at Wandsworth went on sale for £1000 in 2022, logging the fatal days exercise period that started at 2.30 that afternoon, but obviously with a missing entry for his return. Michael Gale was the unfortunate Governor at the time, but the subsequent report attributed no blame to him and he went on to become a member of the Prisons Board.

One of Ronnies fellow escapees was Eric Flower who went over the Wandsworth wall with him in 1965. He was subsequently arrested in Sydney and returned to the UK in 1966. It was suspected that Eric had been in close contact with Ronnie in Australia, but the police were never able to track the great train robber down before he left for Brazil. After 36 years at large and on account of failing health Ronnie returned to the UK and was formally re-arrested in May 2001. He was released from prison on compassionate grounds in August of 2009 and died four years later in a nursing home in December 2013 aged 84.

* * *

The case of George Blake in the 1960’s is very well known. He was born in 1917 Rotterdam to a Jewish family with the surname Behar. For what the family thought was ease of integration into British wartime society, his mother changed the family name in 1944 to Blake, a year after George arrived in England from working with the Dutch resistance. By the time of his arrival in England he had already been partly radicalised to communism by his older cousin whilst living for a time in Egypt, although he kept this side of his sympathies mostly to himself. During the Korean war, he was captured by the North and spent three years in the early 1950’s in captivity. It was during this period that he agreed with his captors to work for the KGB undercover, becoming a double agent. His work for the Soviets was eventually discovered and in 1961 he was given the longest sentence in British criminal history of 42 years. Any notion that Blake’s story might be a romantic jape can be dispelled by the fact that over nine years as a double agent, it is alleged that his betrayals accounted for the death of at least 40 MI6 agents.

During his imprisonment for spying, he was regarded with some favour by the authorities at Wormwood Scrubs due to his co-operative behaviour. In 1966, along with a fellow Irish inmate called Sean Bourke, he planned an inventive escape. Sean was released leaving behind a walkie talkie radio for George. A short time later on the agreed day, George slipped unseen through a broken landing window during an evening association period one Saturday night, shielded by a blanket casually draped over the landing rail. Staff and inmates were watching a film on the wing that evening. There were no bars on the Scrubs landing windows at that time. He dropped down into the grounds to await the arrival of a rope ladder over the wall. Sean was held up by a courting couple snogging under the wall at the point over which the ladder was meant to be thrown. As George was about to give up, the ladder suddenly appeared. Climbing down the other side, George accidently fell the last few feet, broke his wrist and was momentarily knocked unconscious. Despite George’s mishap, Sean drove his captive away in the get-away car but bumped into a stationary vehicle. Not wanting to hang around for an explanation, he sped off to avoid capture. As can be imagined, there was a huge outcry that such a high-profile prisoner had managed to escape. Lying low for two months in the accommodation of his various London communist sympathisers, George’s defection to the East was helped by a couple pretending to go on a continental holiday in a camper van.

With two of the ‘campers’ children and George concealed in a false compartment he made it to the border with East Germany where he gave himself up. The USSR were delighted to see him. He lived in the Soviet Union for 36 years and eventually becoming almost blind, he died at the age of 98 in 2020. Such a serious escape resulted in Lord Mountbatten being called in to lead an Enquiry. His report was delivered to Parliament in December of 1966.

* * *

I’m going to stop using just the Christian name for the next batch of escapers because that almost matey tone is not appropriate for the much more unsavoury group that follows. I don’t want to appear as though I have any sympathy for them by seeming to be over familiar. Roughly three years after Ronnie Biggs escaped from Wandsworth, an intimidating inmate, John McVicar ‘had it away’ from Durham. Despite a relatively normal upbringing by his parents who ran a newsagent’s shop, Mr McVicar was into criminality at a young age. As a 16-year-old in 1956, his thieving got him sent to a Remand Home from where he made his first escape. Following on from this was a two-year spell in Borstal, and on release he turned his attention to violent robberies. In 1964, a further armed robbery earned him a 15-year sentence which he was due to begin at Parkhurst. It’s important to remember that up until 1993 when the security firm Group 4 took over the escort of inmates, prison officers escorted inmates in normal contracted service buses with civilian drivers. Along with 12 other prisoners who had been attending Winchester Assizes, at a pre-arranged signal, the handcuffed inmates attacked the seven uniformed escorting staff and the bus driver. Despite there being an armed police car following the bus, nine of them made it away into the countryside, including Mr McVicar. Only two got clean away, one of whom was Mr McVicar. He remained on the loose for four months and during that period, he continued with further armed robberies, eventually being apprehended. With his original 15-year sentence he got another eight on top, making 23 years in total. He was allocated to the famous 24 cell high-security E wing at Durham which at the time was regarded as escape proof and housed some of the most difficult prisoners in the system. The wing was in the middle of Durham prison, but in 1972 it changed its role to accommodate convicted females and became known as H wing.

Now aged 28 and having only been at Durham for eight months, Mr McVicar planned an escape along with two other prisoners, Walter ‘Angel-face’ Probyn and Joseph Martin. He had built up his strength from regular sessions in the prison gym and at the same time he began work on removing bricks from a shower wall that gave access to a ventilation shaft. The work of removing bricks was concealed by patching up the ever-enlarged hole with papier-Mache in-fill. Once the hole in the shower room was big enough, the prolific offender Mr Probyn, who had assisted Mr McVicar from the start, made his way into the shaft, but found it led into a long empty old cell below with a barred window. More work was needed before any escape because of the need to cut some old bars with a hacksaw blade that Mr Probyn had secreted in his property from another prison. To make it to the ground from the disused room, a rope needed to be secured from an adjacent window that happened to be the library. When it was possible for a body to squeeze through the bars and then down into the yard, Mr McVicar decided to make his break on the 9 October 1966. The three men chose a normal Tuesday evening. With the help of pre-formed knotted sheets and a makeshift grappling hook, they went down the shaft, into the old cell and squeezed through the cut bars of the window and lowered themselves into an open yard. One inmate from E wing who had hoped to be part of the escape team began screaming abuse at the three from his cell window and the staff began to appear in numbers in the grounds. The lifer Mr Martin was caught first on the ground whilst the other two climbed onto a series of roofs. As Mr McVicar managed to find himself high up near an accessible point to the outside wall, Mr Probyn was captured.

Any former plan had to be abandoned and Mr McVicar luckily made it to a roof area near the old Courthouse at the front of the prison. Given he was only 9 feet from the wall top, he was able to negotiate the barbed wire boundary wall with the help of a prison jumper, from where he then dropped down into the street below. It had been a bit of a chaotic escape, but over a couple of days he managed to get well away from Durham to a small village somewhere near Chester-Le-Street. He made telephone contact via a public red phone box, organising a couple of fellow criminals from London to drive north to a prearranged pick-up point. Good fortune saw him avoid capture by minutes. Dishevelled and exhausted, he just managed to rendezvous with his accomplices and was driven to London where he was able to evade capture for some time.

Although the movie “McVicar” with its slightly fanciful script, was released in 1980 about the Durham escape starring Roger Daltrey, Mr McVicar himself seemed not to be a particularly endearing character. His mother described him as ‘difficult’ and other comments about him suggested he mostly held humanity in contempt. He apparently was not a very pleasant individual and it would be misguided to see him as any kind of hero.

He was paroled early in 1978. During his years in prison, he took advantage of advanced educational opportunities and branched out into journalism when released, having gained a range of academic qualifications. Much to Mr McVicar senior’s disappointment, his son Russell followed his father off the rails in a major way and ended up with a lengthy sentence for amongst other things, stealing an £800,000 Picasso from a gallery. In his later years, Mr McVicar led a lonely life. With two failed marriages and estrangement from his only son, he ended up living on his own in a caravan with his dog, behind a pub in Essex. He died of a heart attack in 2022, two years after George Blake.

.PETER ATKINSON, former Governor

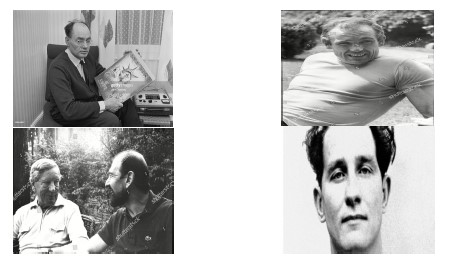

Below are pictures of some of the escapologists whose exploits were detailed by Peter in his piece. Anti-Clockwise from top left to top right:

Alfred Hinds, George Blake (with Kim Philby in the USSR), Ronnie Biggs and John McVicar.