Founded 1980

Chair:

Secretary:

Treasurer:

Graham Smith

Jan Thompson

Graham Mumby-Croft

Issue No. 90 Autumn 2024

Peter Atkinson

Good Riddance or Sad Loss?

By: Peter Atkinson.

Having worked for varying periods in five of these types of prison (Durham, Stafford, Wakefield, Birmingham and Gloucester) at one time or another during a thirty-year period, I can understand their appeal. But what has prompted this article now? Well, it stemmed from a recent casual conversation I had with an old friend and former Governor colleague Peter Quinn, over the question of why some major cities didn’t seem to have any prisons while other small places like Gloucester or Winchester for example did. I happened to mention to Peter that I believed Newcastle had never had a 19th century prison although its next-door neighbour Durham did, whilst York had no prison yet its near neighbour Wakefield did. A little research revealed that in fact Newcastle did have a prison opened in 1828 right in the heart of the city. Peter sent me a picture of Clifford’s Tower in York, attached to which was a radial prison next to the Castle Museum. I found myself drawn into exploring the whole topic of radials and hence this article.

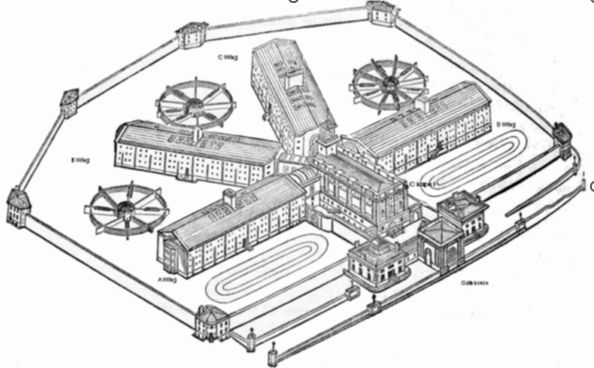

I don’t intend to get bogged down in too much historical detail, but in broad terms a number of historians point to Millbank as being the early 19th century inspiration for the radial prison, with Jeremy Bentham supplying the philosophical and architectural vision. Although Bentham’s original design of the panopticon (central observation tower totally surrounded by tiers of cells facing the tower where staff could see all the inmates without being seen themselves) was not widely adopted, his ideas did however morph into the radial system that is recognisable today. Despite Millbank’s disastrous construction saga involving marshy unstable ground, collapsing walls, disease and exploding windows, the prison eventually took its first inmates in 1816. The layout was actually hexagonal in shape, but this was generally recognised as the precursor to the later radial designs that became commonplace. The prison got quite a lengthy mention by Charles Dickens in ‘Bleak House’, and we’re told by Conan Doyle in ‘The Sign of Four’ that Holmes and Watson crossed the Thames next to the prison. Millbank however was expensive and ill-conceived and it was eventually replaced by Pentonville. I’ll come back to Pentonville but just to clear up a little quirk, Pentonville prison is not actually in Pentonville but is on the Caledonian Road in the Borough of Islington. Before moving on, it is worth a brief reference to Clerkenwell’s Cold Baths Fields prison, built in modern day Islington. Although a prison of some antiquity, it did have a radial structure added to its accommodation as early as 1816 before it too fell out of favour like Millbank and was closed in 1885.

Accepted wisdom suggests that the guiding light for the radial prisons that mutated out of Millbank, was Pentonville, with its four cell blocks of four landings each. An alternative suggestion has been offered that the small, old Fosse Way prison at Northleach in Gloucestershire was the inspiration, (not to be mixed up with the £286 million new prison called Fosse Way on the old Glen Parva site), but hard evidence to support this idea is difficult to find. What was it that stimulated the huge prison building boom from the early 19th century, that resulted in 54 radial prisons constructed across the country in a six-year period following Pentonville, with another 36 before the last quarter of the century? In simple terms, a layman would probably point to six factors: the end of transportation, the end of capital punishment for a range of offences, John Howard’s tireless work in pointing out the appalling state of English prisons, the influence of the great prison reformer Elizabeth Fry, the growth of large industrial cities and rising crime, and last but not least, the Victorian era belief that reasonable prison accommodation plus hard work and religion, could change offending behaviour. The state of county jails across the country up to the early 19th century had been truly disgraceful, and this undoubtedly led to a radical political rethink, leading up to what in effect became the establishment of a nationalised prison system in 1877 with the introduction of the Prison Commission.

I won’t list all the new radial prisons opened between 1816 and 1877, but I will come back to some of them later. Between 1918 and the 2nd World War, thirty-six old prisons closed, but then thirteen of those were re-opened after the War. I’ll look at some of those that have closed more recently, but first let me reference a few little-known prisons that quietly disappeared into obscurity towards the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century.

The long lost, little-known radials that I’ve chosen are Newcastle, York and Derby. Within the city walls but on a piece of green land, the location and construction of Newcastle Gaol caused not a stir within the local community. It was built by the famed local architect John Dobson on a two-acre site at a cost of £33,000 in an area called Carliol Croft. The 25-foot-high walls enclosed five wings with four landings, each radiating out from the elliptical (circular dome) building in the middle. Made with high quality materials, it accommodated a hundred cells, eventually taking its first prisoners in 1828 after a 5-year construction period. The ethos of the prison was to, “improve health and morals”. The Town Council had funded it and organised its operation, but they were relieved to hand it over to the newly formed Prison Commission in 1877. It began to earn a fairly bad reputation and by the turn of the century, there was talk of closing the place. Businesses and dwellings had grown up around this large, dominating, dirty structure and the surrounding land was becoming very valuable. It staggered on until 1925 when the lack of local adult male offenders due to the carnage of the First World War, made it untenable and it was pulled down.

If Newcastle Goal had been built in an uncontroversial part of the city, York’s new prison in 1835 was extraordinary, in that it was built right in the city’s heart, overshadowing the historic Clifford’s Tower. It took ten years to complete and was regarded as the most remarkable and largest building in the surrounding area, competing for prominence with York Minster. There were four radial wings meeting in the middle, part of which formed the Governor’s house. The dark millstone perimeter wall was all encompassing, enclosing Clifford’s Tower. A legitimate comment might be, “what were they thinking?” It only held offenders until 1900 when it was turned into a military detention centre, eventually being closed and then demolished in 1934. Old aerial pictures of it emphasise what many historians and town planners would regard as a crazy, inappropriate, misguided architectural misadventure. On-line there is an impressive photograph from 1934 of the skeletal brick-built prison half demolished, swaddled in rubble with parts of the galleries still visible, and Clifford’s Tower in the background.

Last on the list of the three old radial prisons is Derby. There had been a few prisons in Derby over the centuries, but the New Derby Gaol covering three acres on Vernon Street was a classic radial structure with six wings, each of two storeys that met at a hub which, amongst over things, housed the Governor’s quarters. It had a 25-foot-high perimeter wall made up of 15 courses of brick. Officially known as Vernon Street Prison, it was designed by London architect Francis Goodwin and completed in 1827 at an astonishing cost of £66,212. Francis Goodwin located the prison within an elegant street scape creating the grand Vernon Street looking much like a good example of Regency planning. Despite the prominent title of ‘Vernon Gate’ carved into the stonework above the main prison entrance, the 250-cell gaol was renamed Derby Prison in 1886. The 1881 census shows 303 prisoners living in Derby Gaol, of whom 25 were women. It ran out of prisoners by the end of the First World War and was part demolished in 1919. What buildings remained, served as a military prison for another 10 years before being completely demolished, save for the fine Doric columned gate entrance with its wide façade, which remains to this day. Interestingly enough, there was an abortive plan in the 1990’s to incorporate the façade into the new build Prison Service Headquarters. After its partial demolition, the prison site accommodated Derby Greyhound stadium for many years until that in turn was dismantled to make way for an office complex and apartments.

The three radial prisons above were far from alone in experiencing demolition or abandonment. Before presenting a list of others that met a similar fate, it is important to emphasise that some of the gaols that I’ll name, began life long before the radial design became popular. All of them however had radial extensions added at later dates. I guess that the following list includes prisons of which many people have never heard. I’ll start with Belle Vue gaol in Gorton, Manchester, which was built in 1848 accommodating 329 males and 119 females. It suffered from serious subsidence due to coal mines underneath and was closed in 1888, being demolished in 1892. The land was used as Belle Vue Pleasure Gardens, zoo and greyhound track. Subsequently an extensive housing estate was built on the plot. Carmarthen Gaol began life in 1789 but had a radial extension in 1869. It closed in 1922 and was demolished in 1938 with the site used for Carmarthen council offices. The 210 cell Devizes County House of Corrections was designed by Richard Ingleman in 1811. It closed in 1925 and was demolished in 1927. Fisherton Anger New gaol in Salisbury was built in 1822 with 96 cells for £28,000 and closed in 1870. New Bailey Gaol in Salford with an octagonal four wing formation was built in 1816 but closed in 1868. It was an extremely unhealthy place and was demolished to make way for a railway yard after the inmates were transferred to the new prison at Strangeways.

Knutsford House of Corrections on London Road was more a panopticon than a classic radial, but it was built by the leading English prison designer George Moneypenny behind the splendid looking Court House in 1847. Moneypenny had a hand in the construction of Durham prison where a splendid courthouse eclipses the original prison entrance next door. Knutsford held 700 prisoners in four wings of three stories. It closed in 1914 and was demolished in 1934. St Mary’s prison on St Mary’s island in Chatham was huge with 1135 cells. It was designed by the Surveyor General of Convict prisons Joshua Jebb, and its three wings with four galleries were completed in 1856. It closed in 1892 and was demolished in 1895 with the site today partly occupied by Greenwich University. The four-storey radial Warwick prison on Cape Road was built quite late in 1880 and was closed during the First World War in 1916. It was demolished just over 50 years after it was built. The governor’s house was preserved and became a pub called, funnily enough, the Governor’s House run by Leslie Rose before it too fell victim to the wrecker’s ball. Worcester Gaol on the renamed Castle Street was built in 1813 and in 1838 had 90 cells added in a radial extension of four wings with three storeys, designed by Francis Sandys. It was closed in 1922 having been considered uneconomic by the Prison Commissioners and demolished in the 1930’s.

Before picking up on those more well-known Victorian era radials that have closed recently, it is interesting to reflect on how one fairly narrow type of design more or less dominated the prison landscape, despite the fact that there were dozens of designers who built prisons right across the country. The radial design that we are familiar with does seem to have many advantages for incarcerating large numbers of people in one place. But when thinking about the variety of prison designs that could have been created during the early 19th century, all failed to gain traction as the radial unquestionably cornered the market. Part of the explanation lies in good observation and keen staffing levels. However, during the Victorian era, churches, railway stations, town halls, hospitals, country houses, schools and waterworks didn’t follow any kind of uniform design, so why was prison design relatively harmonised? The architecturally appealing four storey, 400 cell, 1834 Crescent wing at Stafford was an interesting departure from the classic radial, but this building is unique.

The passing of the 19th century radial prisons

By Peter Atkinson August 2023

Demolition of Northallerton prison (reproduced at the foot of the page) by kind permission of Daniel Kitching Photography

Those of us who’ve had a lengthy career in the Prison Service may have at one time or another, served in one of the classic old radial prisons. This type of inmate living area with the cell blocks radiating out from a central hub (the Centre), was regarded at one time as the bedrock of good prisoner accommodation. Staff today may have mixed feelings about these types of jail, with some feeling comfort from the order, safety and visibility whilst others perhaps see them as a design that is seriously outdated. Many of the old radials are coming up to being over 200 years old and that does seem to pose a question about their suitability in a modern Service. Perhaps some old ideas never die in that the privately run Peterborough prison, that was built in 2005, has two radial living blocks.

Permission from Historic England

If we’ve been talking about classic radials in England, it is important to realise that these type of prisons were built all over the Empire as part of colonial rule. I read an article that suggested 100 Victorian radials were constructed by the British across their colonies, but I can’t check whether that’s true. I am however, familiar with four examples and I can begin with the 5,000-inmate capacity panopticon type prison with six spurs that was built in Myanmar in 1887. Called Insein, this prison is in use to this day. Malta had a Pentonville type prison built in 1842 called Corradino just outside Valetta. It was designed by the Superintendent of Public Works, William Lamb Arrowsmith, with a little help from Joshua Jebb and is still working with a population of around 500. With an inmate capacity of 2,000, the strikingly bright red brick Alipore New Gaol in Kolkata was opened around the 1850’s. The wings radiated out from a central watch tower. Being sited on valuable land, it shut down in February 2019, but part of it is preserved to this day as a prison museum.

My final example is perhaps the most interesting. It’s illustrative of the history of transportation to Van Diemen’s land, becoming known as Tasmania in 1856. More than 70,000 convicts were transported to Tasmania between 1804 and 1853, compared to 162,000 to the whole of Australia in the same period. That is a phenomenal number of people to look after in one small corner of the Antipodes. The convicts were put to work for a living, grinding corn on the prison treadwheels, building roads, mining, farming and tree felling. Port Arthur had long been the location for convict labour involved in producing flour in the huge mill on the Tasman Peninsula. It was on this site that the famous Port Arthur convict gaol was built, over three years in the early 1850’s, just as deportation was ending. This radial prison with its design based on Pentonville, was built with four landings on each of the six spurs. It took hardened criminal recidivists who had re-offended after earlier experiences of deportation. Transportation ended in 1853 and this resulted in a steady reduction in the gaol’s population from the high of 1000 inmates in 1853 down to 700 by 1870. It was a question of the convicts becoming old men, which then made the place unsustainable, resulting in its closure in 1880. The buildings that weren’t destroyed by salvage hunters, were further pillaged by bush fires, but remnants of the gutted, old cell blocks did survive and have become a tourist attraction today. An interesting little story relates to this Port Arthur Penal Colony, that is sited at the tip of the narrow Tasman peninsular. It was regarded as virtually escape proof, with high jagged cliffs and three sides protected by the allegedly shark infested waters. Norfolk Bay on one side, Fredrick Henry Bay on another and Storm Bay on the other. At the narrow 30-metre-wide sandy neck of the isthmus called Eaglehawk Neck, there was what was called the “dog line”. The authorities tethered a line of nine vicious dogs on long chains across the narrow strip. Over the loud noise of the sea, the dogs barking not only alerted the guards to the approach of any escaping convict, but they were also a fearful deterrent to the would-be escaper.

Before looking at more recent radial prison closures, a few examples from the past are worth mentioning. Oxford prison was, at one time, quite famous, with a subsequent radial design addition by George Moneypenny in the early 1800’s. It shut down in 1996, remaining empty for 20 years before being turned into a Malmaison hotel. Poor living conditions for the inmates with three to a cell, slopping out and one shower and change of clothes a week, made it a miserable place before closure. Although not wholly a classic radial prison, it did experience Victorian alterations between 1845 and 1877. Lancaster Castle prison had been a gaol for centuries but changed its use in 1916 to holding German prisoners of war. It re-opened as a full prison in 1955 but it too eventually closed for good in 2011.

A slew of closures of some older Victorian/radial prisons took place in 2013 as Michael Gove selected seven prisons to cease trading, calling them, “…old and uneconomic”. Bullwood Hall (not a radial), Camp Hill (not a radial), Canterbury (not strictly speaking a radial), Gloucester, Kingston, the ancient Shepton Mallet and Shrewsbury, all closed their doors for the final time as part of Mr Gove’s decision. Dorchester, Reading and Blundeston (not a radial), happened to close as well in 2013 with Northallerton following suit in 2017. Some of them have become tourist attractions including ghost tours. Others have turned into housing developments. One is an Arts Centre and one has become student accommodation. From the list above, Northallerton seems to be the only prison to have had all its accommodation blocks completely demolished, making way for a Lidl store.

Another fascinating story involves the Victorian prison of Holloway with the once striking and architecturally impressive Gate complex, now gone. It was a classic radial, built in 1852 on Parkhurst Road for male offenders but changed to being a women’s prison in 1903. It developed a very progressive regime under an inspiring and progressive Governor called Joanna Kelley. Important to her ethos was a demolition of the original radial structure that she felt was unsuitable to a non-violent group of female prisoners. Over a ten-year period that started in 1967, the prison was transformed into a more sympathetic set of buildings that softened some of the hard lines. Despite all this, the prison closed in 2016 and is still empty.

Pentonville is another interesting case in its own right. It has always been regarded as the template on which most of the Victorian gaols in England and abroad were based. After some condemnatory reports from various sources, Pentonville was scheduled to close in 2015. Squalid conditions, understaffing, overcrowding, vermin and a notorious escape were all factors outside the control of the staff. Quite simply, the old fabric of the buildings and alleged funding starvation over years, turned a once pioneering prison into a liability. All these things almost condemned the prison beyond reprieve, but it was thrown one last lifeline and a refurbishment programme was arranged following considerable protest from those who thought the prison should be preserved. All the windows were renewed along with other security measures and the prison survives to this day. It is argued that its proposed closure rested as much on the saleable value of the land on which it stood, as it did on all its problems. Many well-known prisons like Pentonville, with the exception of Dartmoor, were originally sited on the edge of the cities to which they belonged. As populations spread, these prisons found themselves in prominent positions as very valuable plots of real estate. Land values as well as crumbling structures, put great pressure on these infamous prisons to be replaced.

Original Design of Pentonville Prison by Joshua Jebb in 1840.

Not having had a mention so far are 18 mid-sized Victorian prisons that are still part of the Prison Service estate today. I won’t name them all, but they include recognisable names like Bristol, Maidstone, Leicester, Nottingham, Lincoln and Exeter (designed by George Moneypenny). They all have their own interesting stories, but just as a little aside, Leicester’s interest lies in its exceptionally high walls that are the highest in England, reaching a height of 30 feet. The Welford Road prison was designed by county surveyor William Parsons in 1825 and cost £20,000.

To conclude, reference has to be made to the major, large radials, chiefly sited in our large cities. Included in this list are Birmingham, Leeds, Durham, Strangeways, Liverpool, Brixton, Wandsworth, Wakefield and Hull, with Dartmoor and Parkhurst as outliers. Not on this list is Wormwood Scrubs on Du Cane Road, that is not actually a radial. With its distinctive entrance, its progressive design was fashioned by Major General Sir Edmund Frederick Du Cane, and mostly built by inmate labour. Eventually opened in 1875 with the inmate accommodation in four-sided blocks, it had an unusual layout. It got its name from the scrubland of felled trees and poor soil quality on which it was built. It was reportedly scheduled by Michael Gove for closure, but pressure on places resulted in a reprieve.

It seems not unreasonable to suggest that all the old, large prisons will probably close before the end of 2040, being regarded as defective, vulnerable to escape, weary and no longer suitable. Replacing them will cost a huge amount of money and cause havoc to the rising inmate population during the transition. The desire by successive governments to get rid of them seems to be high but the practicalities are daunting. With future closures highly likely with most of these prisons, there may be enough old radials consigned to the museum circuit, so that once they have gone as places of incarceration, people will still be able to see for generations to come, what they were like.

PETER ATKINSON