Founded 1980

Chair:

Secretary:

Treasurer:

Graham Smith

Jan Thompson

Graham Mumby-Croft

Paul Laxton

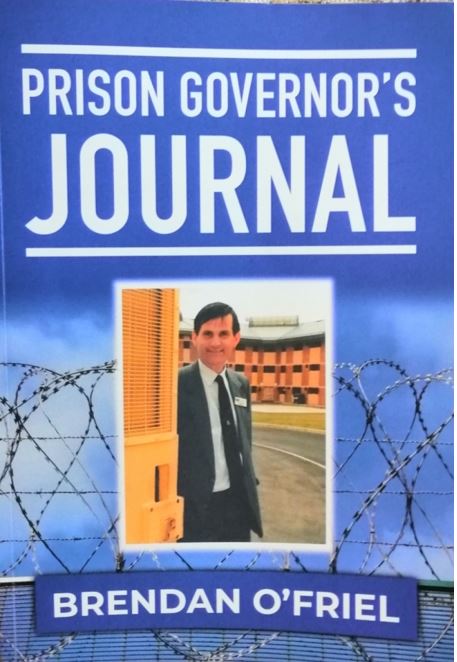

THE DEFINITIVE PRISON SERVICE MEMOIR...

Book Review by Paul Laxton

Perhaps the most surprising thing about Brendan O'Friel's memoirs is the length of time it has

taken for him to have them published, given that he retired as long ago as 1996. Indeed some of

those who are now retired Governors will have joined and retired from the prison service in

between the Strangeways riot of 1990, and the publication of Mr O'Friel's book, 'Prison Governor's

Journal.' It is Brendan O'Friel's misfortune among the wider public to be remembered as the man

whose prison was reduced to rubble in April 1990, in a riot that commenced on All Fools Day, and

dragged out for 25 days. For those of us who were in the service at the time, whether you knew

him or not, the memory is rather different. The man we remember was a leader with strong moral

purpose derived from his staunch Catholic faith, a man regarded as first among equals by his

peers, a man whose aura alone commanded silence when he entered a room.

The Prison Governor's Association of which Mr O'Friel was a founding father and its national leader

for five years, occasionally awards at its Annual Conference an honour known as the 'O'Friel

Phoenix,' to the member or members who have been sorely tried by personal and professional

adversity in the past year. It is well named as Brendan O'Friel found himself at the centre of a

media firestorm, as well as the one consuming his prison. Yet he emerged with his dignity intact

and his reputation heightened. The true villains of the piece, politicians and senior civil servants,

would get their comeuppance when the Woolf Enquiry report was published the following year.

Readers who do not have a ready acquaintance with those 25 days in April, may be astonished to

learn that the then Director General of the Prison Service, Christopher Train, claimed in an

interview that Brendan O'Friel had called off a planned attempt to retake the prison on the second

day of the riot, when the truth was that he was overruled over the telephone by the Deputy Director

General, Brian Emes, in a conversation that took place when Mr Train was in the same room as his

Deputy. Chris Train is long dead and therefore cannot speak for himself, but it is inconceivable that he was not aware of his Deputy's order. Almost as baffling is the fact that emerged later that ministers were not aware of who really made the decision to abort the use of force.

In describing the Strangeways affair, the reader gets a true flavour of the author. Most writers readily deploy either the bludgeon or the sabre when seeking to eviscerate a historic adversary. Mr O'Friel has a very different style, largely letting facts speak for themselves, sparing in his commentary, but unsparing in laying the blame where it belongs. As a co-religionist of the author (in my case a lapsed one), I was brought up never to call anyone a liar. I suspect it was the same for Mr O'Friel, who never actually uses the word, but leads you to an inescapable conclusion. I could say much more about senior civil servants from my own time on the NEC of the Prison Governors Association, but it would not be proper to associate Mr O'Friel, however indirectly, with my views and experiences after his retirement.

The Prison Service is sometimes referred to as the 'fourth emergency service,' and is certainly viewed as the Cinderella service by those who work in it. I think I can safely associate Brendan O'Friel with that view. There are a number of themes that run through the book, but it is clear to me that Prison Overcrowding, and its baleful consequences, is the overriding theme. You would not put bunk beds in a hospital ward, you would not expect patients to eat their meal in a toilet, yet politicians of all stripes not only tolerate these conditions but actively encourage the courts with their rhetoric to further overcrowd already overcrowded local prisons. It is as though the Poor Law, (and most prisoners are poor) and more pertinently its principle of 'less eligibility,' is alive and well in our prison system, rooted like Japanese Knotweed. For Brendan O'Friel overcrowding is a moral issue, because it attacks the moral fabric of the institution itself, degrading staff and prisoners alike. The reader will swiftly draw the conclusion that the main villain is Michael Howard, Home Secretary for the last three years of the author's career, who swiftly reversed the positive momentum generated by his predecessor but one, Kenneth Baker, that followed the publication of the Wolf report in 1991.

Under Michael Howard the prison population doubled, and has remained between 85,000 and 90,000 ever since. No Home Secretary, since 2007 Justice Secretary, dares to seriously challenge the Howard mantra that 'Prison Works,' for fear of being jumped all over by the populist press and perhaps forfeiting the next General Election. Sadly there are no votes in prison reform. At the beginning of the book, Mr O'Friel quotes Winston Churchill; 'The mood and temper of the public in regard to the treatment of crime and criminals is one of the most unfailing tests of the civilisation of any country.' Chapter 14 describes in detail how the country fails that test.

Space does not permit me to comment at length on the other themes of the book. However, the poor industrial relations between the service and the Prison Officers Association are laid bare. I am of the view that an employer gets the trade unions it deserves, but accept that this does not help a hard pressed Governor trying to innovate and improve conditions for prisoners when the main staff association has a very different focus; preserving their earnings by ensuring large amounts of guaranteed overtime regardless of work actually done. The buying out of overtime and premium payments may have improved the health of staff, but it did nothing for their wealth, as successive administrations forced down starting pay. As for privatisation it simply transferred wealth from the workforce to shareholders. Mr O'Friel is excoriating about the treatment of prison officers over the period of his career, not just the absence of proper professional remuneration, but more particularly with regard to the inadequacies of ongoing training and development. In more recent times the Prison Service brought in new terms and conditions that capped the top rate of pay at 5-6k less than those fortunate enough to have joined before 2013. That is after my time, never mind Brendan O'Friel's, and he doesn't need me to point out to him that nothing has changed. The reader may also note that Mr O'Friel is very clear about that which can be blamed on ministers, and that which can be blamed on officials. He is very clear that it is civil servants who are to blame for recurring staffing crises and recruitment failings.

So where does this book stand in the not very well populated pantheon of prison service memoirs? Perhaps surprisingly to some, two of the very best prison service memoirs have been written by former prison officers, Robert Douglas, whose service was in the 60's and 70's, and Neil Samworth, whose service was in the 21st Century. Very different eras and very different books. The Governor's perspective is very different on another level, and the hearing of a voice of great authority and unimpeachable moral integrity is long overdue. Brendan O'Friel has given us a fascinating history of the service over more than three decades through the prism of his own career. Although there is some more demanding reading for those unfamiliar with Prison Service bureaucracy, the book is accessible for the general reader, as well as essential for criminal justice professionals, on whose bookshelves it should have pride of place. It should also be essential reading for MPs,

Treasure this volume, books of this quality are a rare breed.

PAUL LAXTON

Launch:-April2021-https://www.prisongovernorjournal.com/

Available from: - Lexicon Bookshop, 63, Strand Street, Douglas, Isle of Man IM1 2RL 01624 673004

Lexicon Bookshop, 63, Strand Street, Douglas, Isle of Man IM1 2RL 01624 673004

Website: - www.lexiconbookshop.co.im

Issue 84 Spring 2021