Founded 1980

Chair:

Secretary:

Treasurer:

Graham Smith

Jan Thompson

Graham Mumby-Croft

Young Criminals on the March through the East Midlands

***** BREAKING NEWS *****

The good people of Northampton, Market Harborough, Leicester, Broughton Lodge, Gunthorpe and Lowdham have been put at risk by the irresponsible prison authorities as a barely supervised column of young criminals pass through our towns and villages where they are housed overnight in insecure church halls. Their destination is to be an open borstal at Lowdham Grange; a Nottinghamshire country estate within easy walking distance of vulnerable local villages and of Nottingham itself. Why should we be put at risk by importing criminals from London in such away? Criminals who are then to be placed in an institution from which they can easily walk away.

*******

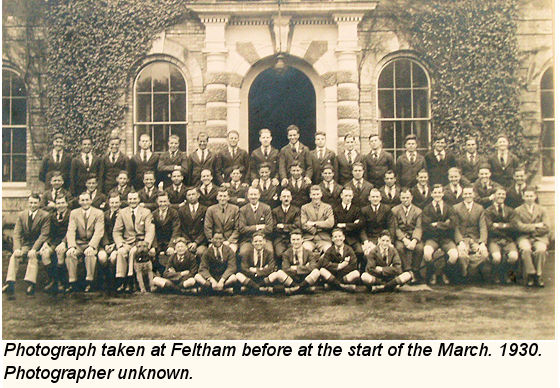

Had they known; then this could have been the leading story in a number of local newspapers in May 1930 as forty borstal lads, aged between sixteen and twenty-one, marched with ten officers from Feltham Borstal in Middlesex to a country estate which nestled on a hillside between the villages of Lowdham, Lambley, Epperstone and Woodborough, some eight miles east of Nottingham. At the time the prison authorities were relieved that after much misrepresentation of the reform aspect of their work; the press were blissfully unaware of their plans and of the march itself. Tom Iremonger MP said in 1962 that this was an epic journey that was still talked about by prison officers. The academic Victor Bailey wrote in 1997 that the March rapidly entered into the folklore of the prison service.

Also, to be considered is that the secure borstal experiment had commenced less than thirty years earlier when a group of lads from London arrived at Feltham - in chains and under armed guard!

So how did it all start? In 1895 a reform-minded Home Office Committee chaired by Herbert Gladstone, son of the prime minister William Ewart Gladstone envisaged a juvenile-offender establishment that was :

“a halfway house between the prison and reformatory …… situated in the country with ample space for agriculture and land reclamation work ... with … penal and coercive sides according to the merits of particular cases … amply provided with staff capable of giving sound education, able to train inmates in various kinds of industrial work, and qualified generally to exercise the best and healthiest kind of moral influence”.

Reform was slow and it was not until 1930 with the opening of the Lowdham Grange Borstal Institution that this aspect of the committee’s work was realised.

Borstals had been developing through a cautious programme; with the conversion of prison wings and reform schools since 1902. And, although a few borstal lads were allowed, usually supervised, out into the community they were locked up at night in secure cells; within secure establishments. This was not to be the case at Lowdham Grange where they could literally climb out of a window or walk through an unlocked door for, as Tom Iremonger MP wrote some thrity years later: the open borstal system placed a great strain and responsibility on its charges through the trust placed upon them. He concluded: “What, after all was their training for?”

But what of the March itself; an ultimate test of trust and responsibility – did it succeed or fail? The prison commissioners had avoided the disaster of the hostile press but what disasters were to befall the marchers, their trusting escorts and their unwitting East Midlands guests?

Harold Scott, a civil servant; future prison commissioner and future commissioner of Scotland Yard, said in his biography

“one day in May 1930 Alec Paterson [a prison commissioner who championed, reform of the prison system and the borstal approach] walked into my room and issued one of his usual abrupt and excited invitations … we are starting a new borstal at Lowdham Grange in Nottinghamshire, and we are going to begin with a little experiment. Bill Llewellin [the deputy governor of Feltham] who is going to be the governor, will lead a party of forty boys on a route march from Feltham to Lowdham. They will spend six days on the road, and will sleep in halls and other places arranged by friends. Would you like to join them? …. I accepted the offer on the spot.”

Paterson personally interviewed the nine staff chosen to participate on the march and they set off with the chosen lads on 4th May 1930. After a church service, photographs and speeches they left Feltham at 9.15 am accompanied by Mr Paterson and arrived at Harrow at 5pm where they were hosted by the local TocH ….. [TocH is an international christian charity which was formed as a soldiers friendship club, just behind the British trenches in Belgium in 1915 – Alec Paterson was a friend of its founder ‘Tubby’ Clayton]. After an uneventful night they left Harrow at 9.30 the following day arriving at St. Albans, again to be hosted by TocH . The lads were treated to a tour of the town and were then entertained by TocH and local scouts before sleeping on the floor, under tables, and in a lorry, having a good nights rest at ‘close quarters’.

On 6th May they washed by the river, cooked breakfast and left St. Albans at 10.30 to arrive at Dunstable at 4.15 where they were entertained and hosted by TocH in the Wesleyan Church Institute. So far so good. They left the next morning to arrive at Newport Pagnell to again be hosted by TocH in the congregational church schoolroom and were entertained by the local scout commissioner. The 8th May saw them leave for Northampton “through beautiful countryside” where according to one lad:

“much courtesy was shown us by passing folk and motorists who always had a friendly nod, or friendly word for us, boy scouts saluted us taking us for fellow scouts and even a policeman on point duty held up traffic for us to pass…..everybody seemed to have a ready smile.”

A thus far uneventful journey saw them arrive at Northampton at 4.15 where they were joined by Harold Scott. They went swimming and had “a lovely tea of teas” at Valentines café. And, were again hosted by TocH and were entertained by a conjuror, jazz band and ventriloquist.

They left Northampton the next morning and spent the night of 4th May in Market Harborough, again hosted by “a warm hearted TocH group”. On 10th May they left for Leicester and were joined by Mr and Mrs Paterson “who handed out bananas… which they had bought especially for us”. They arrived in Leicester at 5pm to be entertained by TocH at Granby Hall after which they went to Aylestone public baths for a wash, swim, change and an inspection. Harold Scott tells how the lads slept in Granby Hall where the Lord Mayor raised a titter when after reviewing the party he cheerfully declared “if I was a bit younger I would like to be in your place”. They spent the Sunday in Leicester attending church and sightseeing. The next morning they were again visited by the Lord Mayor and left to complete their walk. They spent the night of 12th at Broughton Lodge; sleeping in a refreshment hut and to quote one of the lads:

“ ….we had dancing and jazzing … lovely feed of feeds spread out on the table….anyone stepping in would have mistaken us not for borstal boys but for a party of boys on a world tour, happy as sandboys were everyone”.

On 13th May 1930 they marched along the Fosseway in rain and drizzle to have lunch at Gunthorpe. The sun came out as did many of the villagers and the vicar as they entered Lowdham village.

“It seems like all of Lowdham had turned out to see us.”

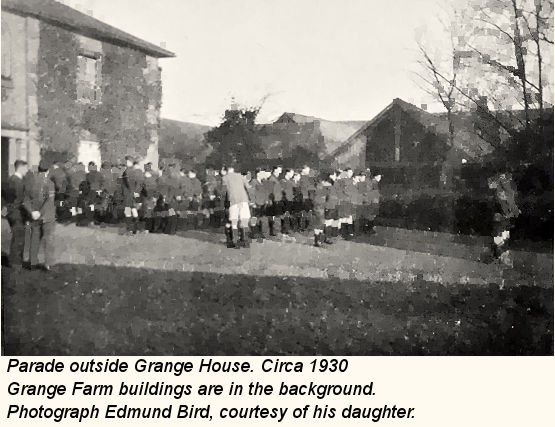

At the gates to Lowdham Grange [on Epperstone Road] they were met by the Bishop of Southwell and other dignitaries. They proudly marched up the hill in good order, craning their necks to see the country house and tents that were to be their new home.

W.W. Llewellyn wrote “…so ended a wonderful ten days [one hundred and sixty two miles]; it has been a happy and inspiring experience for all have shared a common life, entirely out of common for borstal officers and lads ... a petty round of irritating concerns and the jarring contacts of one with another inevitable in a small and closed-penned community. The staff pulled together in an admirable way; a better spirit could not have been wished for. The lads, in conduct, in good manners, in willingness, in unselfishness at all times were ideal; unpleasant incidents, even of a petty nature, were almost entirely absent.”

Victor Bailey also noted that the preparation for the march and the enterprise was as important as the move itself, as it involved a change in the relationship between staff and boys from the although well intentioned, arid strict discipline and punitive regime of existing borstal training. It involved risks for staff who had to:

“look again at the boys with a scrutiny, a hope and an anxiety which could not have been called forth while the staff themselves were not, in a sense, in jeopardy and dependent on the boys loyalty to them”.

Furthermore, the staff on the march would be the first to take the blame for any untoward incidents or inappropriate actions of the boys. He also considered that

“at once the boys and their gaolers became, in however elementary and superficial way, on the same side”.

Alexander Paterson wrote, later in the 1930s that:

‘it is strange thing as the English Lad is a cussed animal, easily led, but driven with much soreness on both sides’.

Harold Scott wrote in his memoires:

“the borstal boys felt proud in the trust we placed in them, and felt themselves to be, for as indeed they were, the pioneers of a great new adventure”

He also wrote that he “never regretted” accepting Alexander Paterson’s invitation to join the march.

Like Lowdham Grange Borstal, the March was a great innovation and success and should be remembered not only for the risk that many in authority and their supporters took; but also for how the young criminals responded to the trust that was placed upon them.

Officers on the March were:

W. W. Llewellin (Governor)

C. T. Cape (Housemaster)

H. J. Taylor (Assistant Housemaster)

H. H. Holmes (Senior Officer)

S. G. Smithson (Officer)

A. T. Perry (Officer)

C. Burns (Officer)

J. H. Marsden (Officer)

E. Young (Driver)

T. W. H Quick (Hospital Officer)

(Hospital Officer)

The officers and lads were to spend the first few years at Lowdham Grange living in tents and wooden huts whilst the lads under the supervision of local tradesmen were to build a borstal institution that was finally demolished in the 1990s; to make way for a modern, secure prison. They also built the housing estate for officers and their families, which still stands and is now in private hands. Lowdham Grange Borstal was an internationally famous innovation in penal history. It received many visits from dignitaries and study groups from across the world and was still spoken about by academics and others at conferences decades later.

Jeremy Lodge