Founded 1980

Chair:

Secretary:

Treasurer:

Graham Smith

Jan Thompson

Graham Mumby-Croft

MANCHESTER WALKS

Issue No. 79 Autumn 2018

David Taylor

It was a very wet Easter Bank Holiday Monday, 1st April, and although I had booked this walk some three weeks earlier, I had not anticipated that it would be quite so wet. The temperature was nothing to write home about either, averaging about 11 degrees Celsius; but all that did not put me off. I should have guessed that the combination of a Bank Holiday and the location of Manchester would not result in a dry day.

On August 16th 2019 it will be 200 years since 16 people were cruelly and savagely cut down in an area of

Manchester called St. Peter’s Fields. Plans are well advanced for the commemorations.

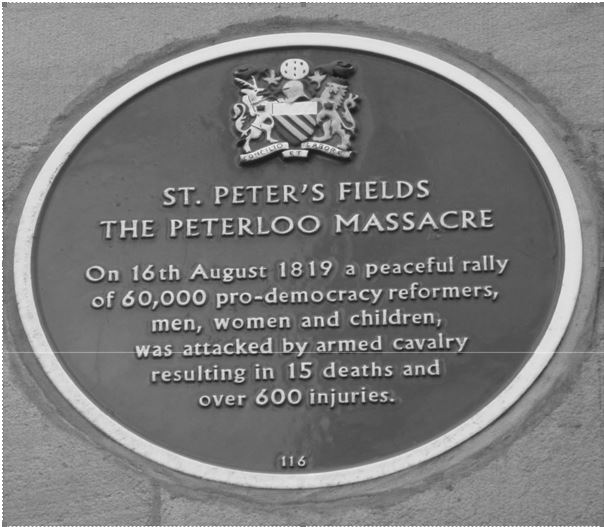

THE PLAQUE THAT NOW HANGS ON THE COLUMN OF THE RADISSON HOTEL IN CENTRAL MANCHESTER.

THE BUILDING WAS ORIGINALLY THE FREE TRADE HALL

About fifty thousand people, some say more, had gathered in an area of Manchester to protest about poverty, in particular the Corn Laws which kept the price of grain artificially high, taking the price of a loaf of bread out of reach for most people. They also came to protest about their right to vote, as at that time not every male person was eligible to vote: in fact it is estimated that only 2% of the population had the right to vote. In the County Palatine of Lancaster, and every other county, if you were eligible to vote you had to travel to Lancaster to raise your hand at an election to have your vote counted: not a fair and equitable system. Henry Hunt and the journalist William Cobbett had begun to campaign for universal suffrage. They argued that extending the vote to working men would lead to better use of public money, fairer taxes and an end to restrictions on trade which damaged industry and caused unemployment.

The crowd came from all over the districts of Manchester and beyond. The meeting was called as a rally might today be called, and the speaker was booked to speak to the crowd. He was a well renowned orator; the equivalent of in modern times in terms of reformers might be Tony Benn or Martin Luther King. This was the very same man campaigning for universal suffrage with William Cobbett, and if you could attract Henry Hunt to your protest then you could be assured of a large crowd.

Lord Liverpool was the Prime Minister of the day and his cabinet consisted of other titled aristocracy. Viscount Castlereagh was the Tory leader in the Commons (there was no such thing as ‘The Conservatives’; this was the day of Whigs and Tories) with Lord Eldon as Chancellor and Lord Sidmouth as Home Secretary.

Europe and the continent of America were recently involved in revolution. It was only 30 years since the French Revolution of 1789 and of course the American Revolution which lasted 24 years had only ceased in 1787, therefore the government of Great Britain was fearful of rebellion and revolution and was wary of public assembly. The great fear was that any revolution would start in Manchester because of the numbers of people in poverty there. The Napoleonic wars had just finished in 1815, income tax was introduced as a way of raising money for the war effort and was deemed as a temporary measure. It still has to be renewed by Parliament every year. It was a time of great suffering as child labour still existed.

So wary of protests were local magistrates and Government that they therefore planned to arrest Henry Hunt and the other speakers at the meeting, and decided to send in armed forces – the only way they felt they could safely get through the large crowd. The enormity of the crowd surprised both the protestors and the Magistrates. This had the air of a peaceful protest, although there were more radical protestors prepared to use violence at other assemblies, with families and bands. This seemed a bright happy gathering of peaceful protest. Banners were carried by men, women and children calling for Equality and Reform, topped with the red cap which was popular in the day.

But according to local magistrates, however, the crowd was not peaceful but had violent, revolutionary intentions. To them, the organised marching, banners and music were more like those of a military regiment, and the practices on local moors like those of an army drilling its recruits. They therefore planned to arrest Henry Hunt and the other speakers at the meeting and decided to send in armed forces – the only way they felt they could safely get through the large crowd. The Magistrates were taking no chances and with the help of the Government assembled 600 Hussars, seven hundred infantrymen, an artillery Unit with two sixpounder guns, four hundred men of the Cheshire Cavalry, and four hundred special constables waited in reserve. There was no official police force at that time.

The time came to disperse the crowd. A small hustings had been set up on which the speakers were to stand. To talk to a crowd of that magnitude without any amplification would have been futile as only the front five rows would have heard the words. The magistrates, watching from the window of a house overlooking both the crowd and the hustings were fearful and decided to read the assembled throng the Riot Act. This is not the epithet it is today. It was the only way the authorities had at their disposal to disperse crowds.

The magistrates then took the fateful decision to order the charge. People who were already cramped, tired and hot panicked as the soldiers rode in, and several were crushed as they tried to escape. Soldiers deliberately slashed at both men and women, especially those who had banners. It was later found that their sabres had been sharpened just before the meeting, suggesting that the massacre had been premeditated.

According to an eye witness the first casualty was a two year old infant being carried in his mother’s arms, slashed down on by a sabre and killed instantly. It must have been a terrifying ordeal for the people involved. Apart from those who died the list of those injured passed 160. News reached the poet P.B. Shelley when he was in Italy and he wrote compassionately in verse about that day. It is entitled ‘The Masque of Anarchy’. The title word ‘Masque’ is meant to portray a mixture of the farce of a pantomime with the hidden cruelty that a mask would conceal. Such masks are worn at protests today. Its’ verse is compelling and emotional. I quote one verse which speaks to the surviving protestors thus:

Rise like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Ye are many – they are few.

That last line sounds vaguely familiar, but the poem is well worth reading against the background outlined here.

There is no doubt that this horrific incident spurred the rate of progress on many reforms, not least of which were the repeal of the Corn Laws and the two Reform acts that followed soon after. This was an event that changed the social history of the country and is as important an event as any other in Britain’s progress to modernity in the nineteenth century. But it is a sad way for reform to happen and we have not learned from history, as it seems in many countries throughout the world the lessons are still to be learned. The best way to finish this is by posting a list of some of those who died that day and in subsequent days.

DAVID TAYLOR